Pack design document.

This is a live document that explains what the thirdweb Pack smart contract is, how it works and can be used, and why it is designed the way it is.

The document is written for technical and non-technical readers. To ask further questions about thirdweb’s Pack contract, please join the thirdweb discord or create a github issue.

Background

The thirdweb Pack contract is a lootbox mechanism. An account can bundle up arbitrary ERC20, ERC721 and ERC1155 tokens into a set of packs. A pack can then be opened in return for a selection of the tokens in the pack. The selection of tokens distributed on opening a pack depends on the relative supply of all tokens in the packs.

IMPORTANT: Pack functions, such as opening of packs, can be costly in terms of gas usage due to random selection of rewards. Please check your gas estimates/usage, and do a trial on testnets before any mainnet deployment.

Product: How packs should work (without web3 terminology)

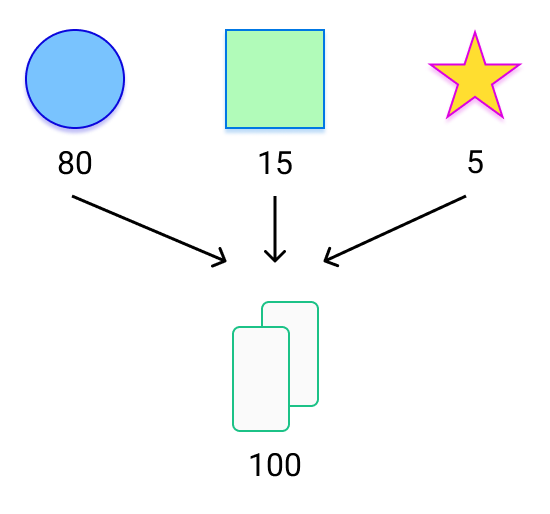

Let's say we want to create a set of packs with three kinds of rewards - 80 circles, 15 squares, and 5 stars — and we want exactly 1 reward to be distributed when a pack is opened.

In this case, with thirdweb’s Pack contract, each pack is guaranteed to yield exactly 1 reward. To deliver this guarantee, the number of packs created is equal to the sum of the supplies of each reward. So, we now have 80 + 15 + 5 i.e. 100 packs at hand.

On opening one of these 100 packs, the opener will receive one of the pack's rewards - either a circle, a square, or a star. The chances of receiving a particular reward is determined by how many of that reward exists across our set of packs.

The percentage chance of receiving a particular kind of reward (e.g. a star) on opening a pack is calculated as:(number_of_stars_packed) / (total number of packs)

In the beginning, 80 circles, 15 squares, and 5 stars exist across our set of 100 packs. That means the chances of receiving a circle upon opening a pack is 80/100 i.e. 80%. Similarly, a pack opener stands a 15% chance of receiving a square, and a 5% chance of receiving a star upon opening a pack.

The chances of receiving each kind of reward change as packs are opened. Let's say one of our 100 packs is opened, yielding a circle. We then have 99 packs remaining, with 79 circles, 15 squares, and 5 stars packed.

For the next pack that is opened, the opener will have a 79/99 i.e. around 79.8% chance of receiving a circle, around 15.2% chance of receiving a square, and around 5.1% chance of receiving a star.

Core parts of Pack as a product

Given the above illustration of ‘how packs should work’, we can now note down certain core parts of the Pack product, that any implementation of Pack should maintain:

- A creator can pack arbitrary ERC20, ERC721 and ERC1155 tokens into a set of packs.

- The % chance of receiving a particular reward on opening a pack should be a function of the relative supplies of the rewards within a pack. That is, opening a pack should not be like a lottery, where there’s an unchanging % chance of being distributed, assigned to rewards in a set of packs.

- A pack opener should not be able to tell beforehand what reward they’ll receive on opening a pack.

- Each pack in a set of packs can be opened whenever the respective pack owner chooses to open the pack.

- Packs must be capable of being transferred and sold on a marketplace.

Why we’re building Pack

Packs are designed to work as generic packs that contain rewards in them, where a pack can be opened to retrieve the rewards in that pack.

Packs like these already exist as e.g. regular Pokemon card packs, or in other forms that use blockchain technology, like NBA Topshot packs. This concept is ubiquitous across various cultures, sectors and products.

As tokens continue to get legitimized as assets / items, we’re bringing ‘packs’ — a long-standing way of gamifying distribution of items — on-chain, as a primitive with a robust implementation that can be used across all chains, and for all kinds of use cases.

Technical details

We’ll now go over the technical details of the Pack contract, with references to the example given in the previous section — ‘How packs work (without web3 terminology)’.

What can be packed in packs?

You can create a set of packs with any combination of any number of ERC20, ERC721 and ERC1155 tokens. For example, you can create a set of packs with 10,000 USDC (ERC20), 1 Bored Ape Yatch Club NFT (ERC721), and 50 of adidas originals’ first NFT (ERC1155).

With strictly non-fungible tokens i.e. ERC721 NFTs, each NFT has a supply of 1. This means if a pack is opened and an ERC721 NFT is selected by the Pack contract to be distributed to the opener, that 1 NFT will be distributed to the opener.

With fungible (ERC20) and semi-fungible (ERC1155) tokens, you must specify how many of those tokens must be distributed on opening a pack, as a unit. For example, if adding 10,000 USDC to a pack, you may specify that 20 USDC, as a unit, are meant to be distributed on opening a pack. This means you’re adding 500 units of 20 USDC to the set of packs you’re creating.

And so, what can be packed in packs are n number of configurations like ‘500 units of 20 USDC’. These configurations are interpreted by the Pack contract as PackContent:

enum TokenType { ERC20, ERC721, ERC1155 }

struct Token {

address assetContract;

TokenType tokenType;

uint256 tokenId;

uint256 totalAmount;

}

uint256 perUnitAmount;

| Value | Description |

|---|---|

| assetContract | The contract address of the token. |

| tokenType | The type of the token -- ERC20 / ERC721 / ERC1155 |

| tokenId | The tokenId of the the token. (Not applicable for ERC20 tokens. The contract will ignore this value for ERC20 tokens.) |

| totalAmount | The total amount of this token packed in the pack. (Not applicable for ERC721 tokens. The contract will always consider this as 1 for ERC721 tokens.) |

| perUnitAmount | The amount of this token to distribute as a unit, on opening a pack. (Not applicable for ERC721 tokens. The contract will always consider this as 1 for ERC721 tokens.) |

Note: A pack can contain different configurations for the same token. For example, the same set of packs can contain ‘500 units of 20 USDC’ and ‘10 units of 1000 USDC’ as two independent types of underlying rewards.

Creating packs

You can create packs with any ERC20, ERC721 or ERC1155 tokens that you own. To create packs, you must specify the following:

/// @dev Creates a pack with the stated contents.

function createPack(

Token[] calldata contents,

uint256[] calldata numOfRewardUnits,

string calldata packUri,

uint128 openStartTimestamp,

uint128 amountDistributedPerOpen,

address recipient

) external

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| contents | Tokens/assets packed in the set of pack. |

| numOfRewardUnits | Number of reward units for each asset, where each reward unit contains per unit amount of corresponding asset. |

| packUri | The (metadata) URI assigned to the packs created. |

| openStartTimestamp | The timestamp after which packs can be opened. |

| amountDistributedPerOpen | The number of reward units distributed per open. |

| recipient | The recipient of the packs created. |

Packs are ERC1155 tokens i.e. NFTs

Packs themselves are ERC1155 tokens. And so, a set of packs created with your tokens is itself identified by a unique tokenId, has an associated metadata URI and a variable supply.

In the example given in the previous section — ‘Non technical overview’, there is a set of 100 packs created, where that entire set of packs is identified by a unique tokenId.

Since packs are ERC1155 tokens, you can publish multiple sets of packs using the same Pack contract.

Supply of packs

When creating packs, you can specify the number of reward units to distribute to the opener on opening a pack. And so, when creating a set of packs, the total number of packs in that set is calculated as:

total_supply_of_packs = (total_reward_units) / (reward_units_to_distribute_per_open)

This guarantees that each pack can be opened to retrieve the intended n reward units from inside the set of packs.

Updating packs

You can add more contents to a created pack, up till the first transfer of packs. No addition can be made post that.

/// @dev Add contents to an existing packId.

function addPackContents(

uint256 packId,

Token[] calldata contents,

uint256[] calldata numOfRewardUnits,

address recipient

) external

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| PackId | The identifier of the pack to add contents to. |

| contents | Tokens/assets packed in the set of pack. |

| numOfRewardUnits | Number of reward units for each asset, where each reward unit contains per unit amount of corresponding asset. |

| recipient | The recipient of the new supply added. Should be the same address used during creation of packs. |

Opening packs

Packs can be opened by owners of packs. A pack owner can open multiple packs at once. ‘Opening a pack’ essentially means burning the pack and receiving the intended n number of reward units from inside the set of packs, in exchange.

function openPack(uint256 packId, uint256 amountToOpen) external;

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| packId | The identifier of the pack to open. |

| amountToOpen | The number of packs to open at once. |

How reward units are selected to distribute on opening packs

We build on the example in the previous section — ‘Non-technical overview’.

Each single square, circle or star is considered as a ‘reward unit’. For example, the 5 stars in the packs may be “5 units of 1000 USDC”, which is represented in the Pack contract by the following information

struct Token {

address assetContract; // USDC address

TokenType tokenType; // TokenType.ERC20

uint256 tokenId; // Not applicable

uint256 totalAmount; // 5000

}

uint256 perUnitAmount; // 1000

The percentage chance of receiving a particular kind of reward (e.g. a star) on opening a pack is calculated as:(number_of_stars_packed) / (total number of packs). Here, number_of_stars_packed refers to the total number of reward units of the star kind inside the set of packs e.g. a total of 5 units of 1000 USDC.

Going back to the example in the previous section — ‘Non-technical overview’. — the supply of the reward units in the relevant set of packs - 80 circles, 15 squares, and 5 stars - can be represented on a number line, from zero to the total supply of packs - in this case, 100.

Whenever a pack is opened, the Pack contract uses a new random number in the range of the total supply of packs to determine what reward unit will be distributed to the pack opener.

In our example case, the Pack contract uses a random number less than 100 to determine whether the pack opener will receive a circle, square or a star.

So e.g. if the random number num is such that 0 <= num < 5, the pack opener will receive a star. Similarly, if 5 <= num < 20, the opener will receive a square, and if 20 <= num < 100, the opener will receive a circle.

Note that given this design, the opener truly has a 5% chance of receiving a star, a 15% chance of receiving a square, and an 80% chance of receiving a circle, as long as the random number used in the selection of the reward unit(s) to distribute is truly random.

The problem with random numbers

From the previous section — ‘How reward units are selected to distribute on opening packs’:

Note that given this design, the opener truly has a 5% chance of receiving a star, a 15% chance of receiving a square, and an 80% chance of receiving a circle, as long as the random number used in the selection of the reward unit(s) to distribute is truly random.

In the event of a pack opening, the random number used in the process affects what unit of reward is selected by the Pack contract to be distributed to the pack owner.

If a pack owner can predict, at any moment, what random number will be used in this process of the contract selecting what unit of reward to distribute on opening a pack at that moment, the pack owner can selectively open their pack at a moment where they’ll receive the reward they want from the pack.

This is a possible critical vulnerability since a core feature of the Pack product offering is the guarantee that each reward unit in a pack has a % probability of being distributed on opening a pack, and that this probability has some integrity (in the common sense way). Being able to predict the random numbers, as described above, overturns this guarantee.

Sourcing random numbers — solution

The Pack contract requires a design where a pack owner cannot possibly predict the random number that will be used in the process of their pack opening.

To ensure the above, we make a simple check in the openPack function:

require(isTrustedForwarder(msg.sender) || _msgSender() == tx.origin, "opener cannot be smart contract");

tx.origin returns the address of the external account that initiated the transaction, of which the openPack function call is a part of.

The above check essentially means that only an external account i.e. an end user wallet, and no smart contract, can open packs. This lets us generate a pseudo random number using block variables, for the purpose of openPack:

uint256 random = uint256(keccak256(abi.encodePacked(_msgSender(), blockhash(block.number - 1), block.difficulty)));

Since only end user wallets can open packs, a pack owner cannot possibly predict the random number that will be used in the process of their pack opening. That is because a pack opener cannot query the result of the random number calculation during a given block, and call openPack within that same block.

We now list the single most important advantage, and consequent trade-off of using this solution:

| Advantage | Trade-off |

|---|---|

| A pack owner cannot possibly predict the random number that will be used in the process of their pack opening. | Only external accounts / EOAs can open packs. Smart contracts cannot open packs. |

Sourcing random numbers — discarded solutions

We’ll now discuss some possible solutions for this design problem along with their trade-offs / why we do not use these solutions:

Using an oracle (e.g. Chainlink VRF)

Using an oracle like Chainlink VRF enables the original design for the

Packcontract: a pack owner can open n number of packs, whenever they want, independent of when the other pack owners choose to open their own packs. All in all — opening n packs becomes a closed isolated event performed by a single pack owner.Why we’re not using this solution:

- Chainlink VRF v1 is only on Ethereum and Polygon, and Chainlink VRF v2 (current version) is only on Ethereum and Binance. As a result, this solution cannot be used by itself across all the chains thirdweb supports (and wants to support).

- Each random number request costs an end user Chainlink’s LINK token — it is costly, and seems like a random requirement for using a thirdweb offering.

Delayed-reveal randomness: rewards for all packs in a set of packs visible all at once By ‘delayed-reveal’ randomness, we mean the following —

- When creating a set of packs, the creator provides (1) an encrypted seed i.e. integer (see the encryption pattern used in thirdweb’s delayed-reveal NFTs), and (2) a future block number.

- The created packs are non-transferrable by any address except the (1) pack creator, or (2) addresses manually approved by the pack creator. This is to let the creator distribute packs as they desire, and is essential for the next step.

- After the specified future block number passes, the creator submits the unencrypted seed to the

Packcontract. Whenever a pack owner now opens a pack, we calculate the random number to be used in the opening process as follows:uint256 random = uint(keccak256(seed, msg.sender, blockhash(storedBlockNumber)));- No one can predict the block hash of the stored future block unless the pack creator is the miner of the block with that block number (highly unlikely).

- The seed is controlled by the creator, submitted at the time of pack creation, and cannot be changed after submission.

- Since packs are non-transferrable in the way described above, as long as the pack opener is not approved to transfer packs, the opener cannot manipulate the value of

randomby transferring packs to a desirable address and then opening the pack from that address. Why we’re not using this solution:

- Active involvement from the pack creator. They’re trusted to reveal the unencrypted seed once packs are eligible to be opened.

- Packs must be non-transferrable in the way described above, which means they can’t be purchased on a marketplace, etc. Lack of a built-in distribution mechanism for the packs.